Can a Baby Be Born Addicted to Methadone?

Managing infants built-in to mothers who accept used opioids during pregnancy

Podcast

Posted: May 11, 2018 | Updated: October 3, 2019

Principal author(s)

Thierry Lacaze-Masmonteil, Pat O'Flaherty; Canadian Paediatric Gild. Updated by Thierry Lacaze-Masmonteil, Fetus and Newborn Committee

Paediatr Child Wellness 2020 23(3): 220–226.

Abstruse

The incidence of babe opioid withdrawal has grown speedily in many countries, including Canada, in the last decade, presenting significant health and early encephalon development concerns. Increased prenatal exposure to opioids reflects rising prescription opioid use as well as the presence of both illegal opiates and opioid-substitution therapies. Infants are at high take a chance for experiencing symptoms of abstinence or withdrawal that may require assessment and treatment. This do point focuses specifically on the effect(s) of opioid withdrawal and current management strategies in the care of infants born to mothers with opioid dependency.

Keywords: Discharge planning; Management; NAS; NPI; Treatment strategies

BACKGROUND

For 2016–17, the Canadian Plant for Health Information reported that an estimated 0.51% of all infants born in Canada (approximately 1850/year, Quebec excluded) had Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS). A large percentage of these cases are attributed to opioid withdrawal [1]. The average length of stay in acute care facilities for these infants was 15 days. Recent reports indicate the number of infants requiring observation for withdrawal symptoms is increasing annually and that cases are mostly nether-reported [2]. The costs of hospitalization speak to the significant burden this trouble places on the wellness of mothers, infants and families, along with hospital units, health intendance providers and other community resources [three].

Opioid use during pregnancy, whether prescribed or illicit, tin can be associated with negative pregnancy and infant outcomes, including prematurity, low nascence weight, increased risk of spontaneous abortion, sudden infant death syndrome and babe neurobehavioural abnormalities [4]. Natural compounds include morphine and codeine. Heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone and buprenorphine are semi-synthetic. Fentanyl, methadone, normethadone, tramadol and meperidine are synthetic [5]. The most significant furnishings of maternal opioid dependence and prenatal fetal exposure are curt-term complications, with NAS predominating. NAS is a set of drug withdrawal symptoms that tin impact the fundamental nervous system (CNS), and the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems in the newborn [six]. Potential long-term outcomes of prenatal opiate exposure are difficult to predict due to multiple, interrelated variables of maternal-infant risk factors that are known to impact developmental outcomes in this accomplice [7][8].

Pregnant women with an opioid dependence should be advised to continue or commence an opioid maintenance therapy plan [9]. Methadone is often recommended for opioid-dependent pregnant women [10] and some studies suggest buprenorphine equally an culling treatment [11]. The literature reports that opioid commutation therapy during pregnancy may lessen the utilise of other opioids and illicit drugs and improve prenatal care, including access to education, counselling and community supportive services [12][xiii]. Obtaining a comprehensive medication or illicit substance use history and a focused social history are recommended. Other associated health risks include infections (e.thou., hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis and HIV), insufficient maternal diet or access to antenatal care, too as social take a chance factors, and should exist screened for, determined and managed appropriately.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

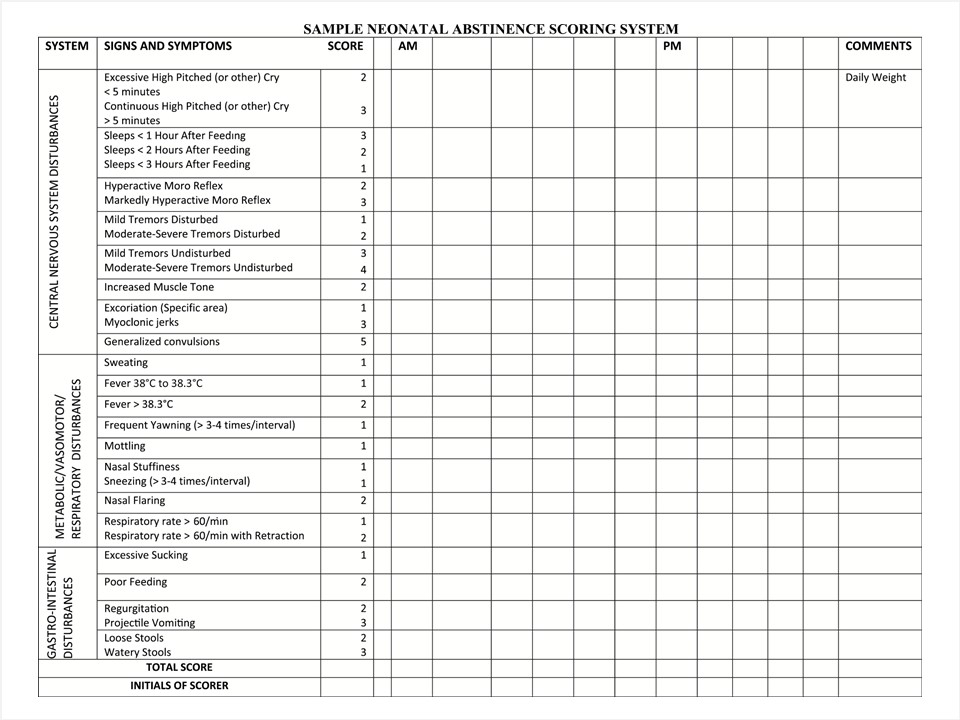

The presentation of withdrawal symptoms varies, depending on the type of maternal opioid used, the frequency, dose and timing of terminal exposure, gestational age, maternal metabolism and maternal use of other substances. Approximately 50% to 75% of infants born to women on opioids will require handling for opioid withdrawal symptoms [14]. Symptoms of opioid withdrawal (Figure i) typically appear presently afterward birth, with the majority exhibited within the first 48 h to 72 h postdelivery. Some reports suggest a later symptom presentation, at 5 to 7 days postbirth, after exposure to methadone or buprenorphine [xv][16]. Initial acute symptoms may persist for several weeks (ranging from x to 30 days) while milder symptoms, such as irritability, sleep disorders and feeding bug can persist for iv to half-dozen months [17]. Preterm infants accept been described as being at lower take chances for drug withdrawal and symptoms of NAS may non exist as credible every bit in their term counterparts [18][nineteen]. Reasons for this difference include: a shorter in utero exposure time, decreased placental transmission, disability to fully excrete drugs by immature kidneys and liver, minimal fat stores leading to lower opioid deposition and action, also equally a limited capacity to express archetype NAS symptoms past the immature brain [19].

|

| Effigy 1. Modified Finnegan scoring system. Reproduced from refs. [15][20][21]. |

Other neonatal weather such every bit hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, CNS injury, hyperthyroidism, bacterial sepsis or other infections may present with similar symptoms and should exist considered as function of the differential diagnosis.

ASSESSMENT

For all opioid-exposed infants, an assessment scoring system should exist used to measure out the severity of withdrawal symptoms and help decide whether additional monitoring, nursing, medical and pharmacological therapy are required [xx]. The virtually widely used scale to evaluate infants for opioid withdrawal is the Finnegan scoring system, which identifies behaviours associated with withdrawal (Figure i) [21]. An initial score is typically obtained within the kickoff 1 h to 2 h postdelivery, then rechecked every three h to iv h thereafter, in conjunction with other nursing assessments. Most guidelines advise that scoring should be done for a minimum of 72 h and up to 120 h when an babe was exposed in utero to a longer-interim opioid, such equally methadone or buprenorphine [nineteen]. The scale may also be used to appraise the resolution of symptoms later initiating treatment. Accurate, consistent scoring of symptoms is necessary to ensure that the babe receives appropriate intendance [22]. A variety of instructional videos and "railroad train-the-trainer" approaches are available to ensure that staff teaching is consistent for proper scoring [23]. Priorities are to develop a standardized process to identify, manage and evaluate infants with NAS, and then to discharge them equally soon equally information technology is rubber and advisable.

MANAGEMENT

Successful supportive management of infants exposed to opioids during pregnancy depends on a number of factors, such as providing advisable medication(s), correct scheduling, using an accurate tool to mensurate and evaluate the severity of symptoms, creating a compatible concrete environment and having a knowledgeable, experienced wellness care squad. Involving interprofessional team members, (i.e., specialized in nursing, neonatal medicine, social work, chemist's shop, nutrition and customs resource) is essential for ensuring the seamless management and discharge of these vulnerable infants [15]. Treatment goals include preventing complications associated with NAS and restoring normal newborn activities, such as slumber, sufficient feeding, weight gain and ecology adaptation.

In addition to maternal self-reporting, some practitioners conduct urine or meconium toxicology screens for infants born to women with a suspected history of drug abuse during pregnancy. This information may be helpful to identify the substance(south) of corruption and for selecting appropriate pharmacological treatment, when required [xvi]. However, the validity and reliability of toxicology testing is controversial [24]. Further, obtaining maternal consent for testing, securing knowledge of who will have access to the results and other legal considerations are important in the decision to conduct or send toxicology screens [25]. National neonatal resuscitation guidelines suggest that using naloxone during babe resuscitation should be avoided when an infant is born to a known opioid-dependent mother because information technology has been associated with seizures in newborns [26]. There is no evidence to propose that a higher than routine level of health care practitioner (HCP) intendance competency is required at commitment, provided there are no other risk factors present.

It is well known that separating infant and mother can be detrimental to early attachment. Recent literature supports practices that keep opioid-dependent mothers and their infants together from birth, such as rooming-in. Such practices have boosted benefits, such equally lower neonatal intensive care unit of measurement (NICU) admissions, higher breastfeeding initiation rates, less need for pharmacotherapy and shorter infirmary stays [27]–[30]. A rooming-in model of care—rather than admission to NICU—tin can be considered for mother–infant dyads at run a risk for developing NAS symptoms when: infants are term or near term, medically stable, and acceptable resources are in place to support both the family and HCPs.

Nonpharmacological interventions

Initial treatment for neonatal withdrawal should be primarily supportive because medical interventions can prolong hospitalization, disrupt mother–baby attachment and subject an infant to drugs that may not be necessary. Nonpharmacological interventions accept been shown to reduce the furnishings of withdrawal and should be implemented equally soon as possible following birth [2]. Examples of supportive interventions include peel-to-skin contact, safe swaddling, gentle waking, quiet environment, minimal stimulation, lower lighting, developmental positioning, music or massage therapy [31].

Breastfeeding should be encouraged considering it can delay the onset and decrease the severity of withdrawal symptoms as well as decrease the need for pharmacological treatment [32]. HIV-negative mothers who are stable and on opioid maintenance treatment with either methadone or buprenorphine should be encouraged to breastfeed [9]. Breastfeeding provides optimal nutrition, promotes maternal–infant attachment and facilitates parenting competence. Mothers with a dependency who wish to breastfeed may require actress back up equally they are less likely to initiate breastfeeding successfully and more than likely to stop breastfeeding early on [33].

NAS infants may show impaired feeding behaviours such as excessive non-nutritive sucking, poor feeding, regurgitation and diarrhea [34]. An early written report [35] found that opioid-exposed infants had more feeding bug (rejecting the nipple, dribbling milk, hiccoughing, spitting up, and coughing) than nondrug-exposed infants. More contempo studies accept confirmed these findings and described the challenges caregivers face when feeding infants who show signs of withdrawal [36]. Supplementation with concentrate to increment caloric intake or full fluid intake has been suggested for infants with poor weight gain [37].

Pharmacological interventions

Pharmacological therapy is indicated for infants whose withdrawal signs are increasingly severe or whose concurrent NAS scores climb despite supportive measures to reduce and manage symptoms. Infants who crave treatment with medications may also crave admission to a special care plant nursery or NICU for cardiorespiratory monitoring and ascertainment while therapy is initiated, particularly if they are medically unstable. A stabilized infant tin be transferred back into a intendance-by-parent surface area (e.chiliad., rooming-in) provided that assessment, parent instruction and medication weaning monitoring are ongoing, infant–mother zipper is supported and comprehensive belch planning tin be initiated [29]. Rooming-in with mothers on a methadone programme and breastfeeding have been shown to reduce the need for pharmacological intervention [thirty].

Several pharmacological agents have been used to ameliorate symptoms associated with neonatal opioid withdrawal (Table 1). Few studies have examined pharmacotherapy efficacy. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends matching drug selection to the blazon of agent causing withdrawal [19]. Morphine and methadone remain the most common first-line medications, with lack of show for which agent is superior [38]. Compared with oral morphine, sublingual buprenorphine has recently been shown to reduce length of stay in hospital past 42% in symptomatic infants born to mothers on methadone [39]. Adjunctive employ of phenobarbital or clonidine therapy to treat opioid withdrawal has been studied and implemented in some guidelines [40][41]. Published guidelines provide information on initial dosing, dosing increments, initiating additional treatments and weaning, to assist in a consistent approach to management [42].

DISCHARGE CONSIDERATIONS

Length of stay in infirmary varies depending on prenatal drug(southward) exposure, severity of withdrawal, symptoms, treatment and social factors [42]. Observe for a minimum of 72 h. If the treatment threshold is not reached within that time, the infant becomes eligible for discharge [43]. The key to successful transition dwelling house is to ensure continuity of care by an interprofessional squad, with anticipatory planning for when the infant meets criteria for discharge.

Individualized discharge planning should include appropriate referral to a principal wellness care provider familiar with pharmacological treatments for opioid withdrawal, nutritional and family supportive resources and infant neurodevelopmental assessment. Communicating with the infant'southward biological (or where necessary, foster intendance) family and the primary HCP well-nigh the discharge programme and follow-up is essential. In some situations, when adequate medical and social follow-upwardly is available, infants may exist discharged habitation on pharmacological support [44][45]. There are a few studies, for a select grouping of infants, which have demonstrated that infants tin can be managed safely in an outpatient setting without increasing treatment time [46]. Benefits of domicile-based detoxification include: decreasing length of hospital stay and associated wellness care costs, promoting infant–caretaker zipper and increasing breastfeeding rates [47]. Of course, these benefits must be weighed against possible risks. Before discharge, the infant should be demonstrating tolerance of pharmacological tapering, with consistent withdrawal scores < 8. Also, a clear, documented medications weaning plan should be in place for the HCP and family to follow. Other community referrals to consider may include ongoing maternal substance abuse treatment programs, public health and child and youth services, a community support worker, baby development programs and/or parenting support groups. Likewise, the families and/or guardians must bear witness they tin can provide a supportive and safety home environment [48].

| Table 1. Medications to treat neonatal forbearance syndrome | |||

| Medication | Machinery of action | Dose | Comments |

| Morphine | Natural m -receptor agonist | If score is ≥ viii on three (or ≥ 12 on 2) consecutive evaluations, start at 0.32 mg/kg/twenty-four hours, divided every 4 h–6 h, orally. | Nigh commonly used every bit first-line handling in Canada |

| Methadone | Synthetic complete m-receptor agonist; North-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist | 0.05–0.ane mg/kg/dose every half-dozen h–12 h, orally | Long half-life (26 h) Used in many countries every bit a first-line handling (instead of morphine) when mother is on methadone. |

| Phenobarbital | Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor agonist | May be used in addition to morphine, especially in poly-substance abuse cases. Loading dose: 10 mg/kg, orally, every 12 h for three doses Maintenance dose: 5 mg/kg/solar day, orally. Wean by 10% to xx% every day or every 2 days when symptoms are controlled. | Long half-life (45 h–100 h) Requires claret level monitoring May make GI symptoms worse Sedative effect Contains 15% alcohol |

| Clonidine | Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist | Culling therapeutic option in combination with morphine. Especially constructive when autonomic symptoms of NAS are present. Get-go at 0.5 mcg/kg for the first dose. The recommended maintenance dose is 3–five mcg/kg/day divided every iv–vi h. Wean past 25% of the total daily dose every other day (Q4h to Q6h × 48h, to Q8h × 48h, to Q12h × 48h to HS, then d/c) | Alcohol-gratis training available Long half-life (44 h–72 h) Abrupt discontinuation may cause rapid rising in blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR). Gradual weaning is therefore recommended. |

| Buprenorphine | Semi-synthetic partial k-receptor agonist, k-receptor antagonist | four–v mcg/kg/dose every viii h; sublingual route Maximum dose threescore mcg/kg/day | Half-life (24 h–60 h) Sublingual assistants of a dilution of buprenorphine solution in ethanol and sucrose Contains thirty% alcohol |

| Information taken from ref. [nineteen]. d/c, discontinue; HS, bedtime. | |||

Summary

Opioid-dependent mothers should be informed that their infant, who has been exposed to natural, semi-constructed or synthetic opioids during pregnancy, will require ascertainment for symptoms and signs of neonatal withdrawal following birth. Antenatal consultation by perinatology, paediatrics and/or neonatology is encouraged.

All infants at take a chance for developing neonatal opioid withdrawal should be evaluated using a reliable, valid neonatal withdrawal score instrument.

Information and guidelines for HCPs on managing infants born to opioid-dependent mothers should outline the continuum of care. Strategies to support keeping mothers and infants together and breastfeeding are essential. Providing nonpharmacological interventions, such as pare-to-skin contact, developmental positioning, comfort measures, minimizing environmental stimuli, ensuring adequate nutrition and providing pharmacological treatment when indicated, are key components of a comprehensive programme.

An effective and well-coordinated discharge plan that involves an interprofessional health care team and outlines a comprehensive medications weaning schedule, is essential to ensure seamless transition from infirmary to community, and for maintaining continuity of intendance.

Acknowledgements

This practice indicate was reviewed past the Community Paediatrics, Drug Therapy and Hazardous Substances and First Nations, Inuit and Métis Wellness Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society. It has also been reviewed by representatives from the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada.

CPS FETUS AND NEWBORN Commission

Members: Mireille Guillot MD, Leonora Hendson MD, Ann Jefferies MD (past Chair), Thierry Lacaze-Masmonteil Medico (Chair), Brigitte Lemyre MD, Michael Narvey Doc, Leigh Anne Newhook Md (Board Representative), Vibhuti Shah Physician

Liaisons: Radha Chari Doctor, The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada; James Cummings Md, Commission on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics; William Ehman MD, College of Family Physicians of Canada; Roxanne Laforge RN, Canadian Perinatal Programs Coalition; Chantal Nelson PhD, Public Health Agency of Canada; Eugene H Ng Dr., CPS Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine Department; Doris Sawatzky-Dickson RN, Canadian Association of Neonatal Nurses

Principal authors: Thierry Lacaze-Masmonteil MD, Pat O'Flaherty MEd, MN, RN-EC

Updated past:Thierry Lacaze-Masmonteil Doctor

References

- Turner SD, Gomes T, Camacho X et al. Neonatal opioid withdrawal and antenatal opioid prescribing. CMAJ Open Research 2015;three(1):E55-61.

- Dow K, Ordean A, Spud-Oikonen J et al.; Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Work Group. Neonatal forbearance syndrome clinical practice guidelines for Ontario. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2012;nineteen(3):e488–506.

- Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000-2009. JAMA 2012;307(18):1934–40.

- Vucinovic M, Roje D, Vucinovic Z, Capkun V, Bucat M, Banovic I. Maternal and neonatal effects of substance abuse during pregnancy: Our ten-year feel. Yonsei Med J 2008;49(five):705–13.

- Opiate Addiction and Treatment Resource. www.opiateaddictionresource.com/opiates/types_of_opioids (Accessed August 22, 2017).

- Finnegan LP. Substance Abuse in Canada: Licit and Illicit Drug Use During Pregnancy; Maternal, Neonatal and Early Childhood Consequences. Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2013: www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/CCSA-Drug-Use-during-Pregnancy-Written report-2013-en.pdf (Accessed August 3, 2017).

- Logan BA, Brown MS, Hayes MJ. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Handling and pediatric outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2013;56(1):186–92.

- Behnke One thousand, Smith VC; Committee on Substance Abuse; Commission on Fetus and Newborn. Prenatal substance abuse: Short- and long-term furnishings on the exposed fetus. Pediatrics 2013;131(3):e1009–24.

- WHO. Guidelines for the Identification and Direction of Substance Utilise and Substance Employ Disorders in Pregnancy. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/107130/ane/9789241548731_eng.pdf (Accessed August three, 2017).

- Wong S, Ordean A, Kahan M; Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee; Family Physicians Advisory Committee; Doc-legal Commission; Ad hoc Reviewers; Special Contributors. Substance use in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011;33(4):367–84. www.researchgate.net/publication/51059321_Substance_use_in_pregnancy (Accessed August 3, 2017).

- Jones HE, Finnegan LP, Kaltenbach K. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence in pregnancy. Drugs 2012;72(6):747–57.

- Ordean A, Kahan M, Graves L, Abrahams R, Boyajian T. Integrated care for pregnant women on methadone maintenance treatment: Canadian primary care cohort study. Tin Fam Physician 2013;59(x):e462–9.

- Burns L, Mattick RP, Lim 1000, Wallace C. Methadone in pregnancy: Treatment memory and neonatal outcomes. Addiction 2007;102(2):264–70.

- Casper T, Arbour M. Testify-based nurse-driven interventions for the care of newborns with neonatal forbearance syndrome. Adv Neonatal Care 2014;14(6):376–80.

- Ordean A, Chisamore BC. Clinical presentation and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome: An update. Res Rep Neonatol 2014;4:75–86. www.dovepress.com/clinical-presentation-and-management-of-neonatal-abstinence-syndrome-a-peer-reviewed-total-text-article-RRN (Accessed August iii, 2017).

- Kocherlakota P. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics 2014;134(2):e547–61.

- Coyle MG, Ferguson A, Lagasse L, Oh Westward, Lester B. Diluted tincture of opium (DTO) and phenobarbital versus DTO lonely for neonatal opiate withdrawal in term infants. J Pediatr 2002;140(v):561–iv.

- Ruwanpathirana R, Abdel-Latif ME, Burns L, et al. Prematurity reduces the severity and need for treatment of neonatal forbearance syndrome. Acta Paediatr 2015;104(5):e188–94.

- Hudak ML, Tan RC; Commission on Drugs; Committee on Fetus and Newborn; American University of Pediatrics. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics 2012;129(two):e540–sixty.

- Newnam KM. The right tool at the right time: Examining the evidence surrounding measurement of neonatal forbearance syndrome. Adv Neonatal Care 2014;14(iii):181–6.

- Finnegan LP, Kron RE, Connaughton JF, Emich JP. Cess and treatment of abstinence in the infant of the drug-dependent female parent. Int J Clin Pharmacol Biopharm 1975;12(1–ii):xix–32.

- Asti L, Magers JS, Keels East, Wispe J, McClead RE. A quality improvement project to reduce length of stay for neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics 2015;135(6):e1494–500.

- D'Apolito K, Finnegan LP. Assessing Signs and Symptoms of Neonatal Abstinence Using the Finnegan Scoring Tool: An Inter-observer Reliability Program. 2d ed. Nashville, TN: NeoAdvances, 2010.

- Pulatie G. The legality of drug-testing procedures for pregnant women. Virtual Mentor 2008;10(one):41–4.

- Levy S, Siqueira LM, Ammerman SD et al.; Commission on Substance Abuse. Testing for drugs of corruption in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2014;133(half dozen):e1798–1807.

- Gibbs J, Newson T, Williams J, Davidson DC. Naloxone take chances in infant of opioid abuser. Lancet 1989;ii(8655):159–60.

- McKnight S, Coo H, Davies G et al. Rooming-in for infants at risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Am J Perinatol 2016;33(5):495–501.

- MacMillan KDL, Rendon CP, Verma K, Riblet North, Washer DB, Volpe Holmes A. Association of rooming-in with outcomes for neonatal forbearance syndrome: a systematic review and meta-assay. JAMA Pediatr 2018 [Epub ahead of impress]. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5195.

- Holmes AV, Atwood EC, Whalen B, et al. Rooming-in to treat neonatal forbearance syndrome: Improved family-centered care at lower price. Pediatrics 2016;137(6):e20152929.

- Hodgson ZG, Abrahams RR. A rooming-in program to mitigate the need to treat for opiate withdrawal in the newborn. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34(5):475–81.

- Jansson LM, Velez M, Harrow C. The opioid-exposed newborn: Assessment and pharmacologic management. J Opioid Manag 2009;5(ane):47–55.

- Abdel-Latif ME, Pinner J, Clews S, Cooke F, Lui K, Oei J. Effects of breast milk on the severity and upshot of neonatal forbearance syndrome among infants of drug-dependent mothers. Pediatrics 2006;117(vi):e1163–ix.

- Wachman EM, Byun J, Philipp BL. Breastfeeding rates among mothers of infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Breastfeed Med 2010;5(4):159–64.

- Maguire DJ, Rowe MA, Leap H, Elliott AF. Patterns of confusing feeding behaviors in infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Adv Neonatal Care 2015;fifteen(six):429–39; quiz E1–2.

- LaGasse LL, Messinger D, Lester BM, et al. Prenatal drug exposure and maternal and infant feeding behaviour. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003;88(5):F391–9.

- Irish potato-Oikonen J, Brownlee Yard, Montelpare W, Gerlach K. The experiences of NICU nurses in caring for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Neonatal Netw 2010;29(5):307–13.

- MacMullen NJ, Dulski LA, Blobaum P. Evidence-based interventions for neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatr Nurs 2014;xl(4):165–72, 203.

- Bagley SM, Wachman EM, Holland Due east, Brogly SB. Review of the cess and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2014;9(1):xix

- Kraft WK, Adeniyi-Jones SC, Chervoneva I et al. Buprenorphine for the treatment of the neonatal forbearance syndrome. N Engl J Med 2017;376(24):2341–8.

- Kraft WK, Stover MW, Davis JM. Neonatal forbearance syndrome: Pharmacologic strategies for the mother and infant. Semin Perinatol 2016;40(3):203–12.

- Streetz VN, Gildon BL, Thompson DF. Role of clonidine in neonatal abstinence syndrome: A systematic review. Ann Pharmacother 2016;50(4):301–10.

- Smirk CL, Bowman E, Doyle LW, Kamlin CO. How long should infants at risk of drug withdrawal be monitored after nascency? J Paediatr Kid Wellness 2014;l(v):352–five.

- Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Wellness. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) Clinical Practice Guidelines. July 19, 2011 (revised March xxx, 2012): https://pqcnc-documents.s3.amazonaws.com/nas/nasresources/NASGuidelines.pdf (Accessed August 3, 2017).

- Smirk CL, Bowman E, Doyle LW, Kamlin O. Abode-based detoxification for neonatal forbearance syndrome reduces length of hospital admission without prolonging treatment. Acta Paediatr 2014;103(6):601–iv.

- McQueen Chiliad, Spud-Oikonen J. Neonatal forbearance syndrome. N Engl J Med 2016;375(25):2468–79.

- Backes CH, Backes CR, Gardner D, Nankervis CA, Giannone PJ, Cordero L. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Transitioning methadone-treated infants from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Perinatol 2012;32(6):425–30.

- Marcellus L, Loutit T, Cantankerous S. A national survey of the nursing care of infants with prenatal substance exposure in Canadian NICUs. Adv Neonatal Care 2015;15(5):336–44.

- Johnston A, Metayer J, Robinson Due east. Direction of Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal. Section four of Treatment of Opioid Dependence in Pregnancy: Vermont Guidelines. Vermont Children's Hospital at Fletcher Allen Health Intendance, 2010. http://contentmanager.med.uvm.edu/docs/default-source/vchip-documents/vchip_5neonatal_guidelines.pdf ?sfvrsn=ii (Accessed August 3, 2017).

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not bespeak an exclusive grade of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be advisable. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

Source: https://cps.ca/documents/position/opioids-during-pregnancy

0 Response to "Can a Baby Be Born Addicted to Methadone?"

Post a Comment